Is It Valid To Study Aging Pathologies In Young Animals?

- Editorial

- Published:

The importance of aging in cancer research

Nature Aging book 2,pages 365–366 (2022)Cite this article

Cancer is a disease of aging, but information technology is rarely studied in anile animal models and older adults are oftentimes insufficiently represented in cancer clinical trials. To further our agreement of cancer and find ameliorate treatments, more research is needed on the role of biological crumbling in cancer and clinical trials must enroll larger numbers of older patients.

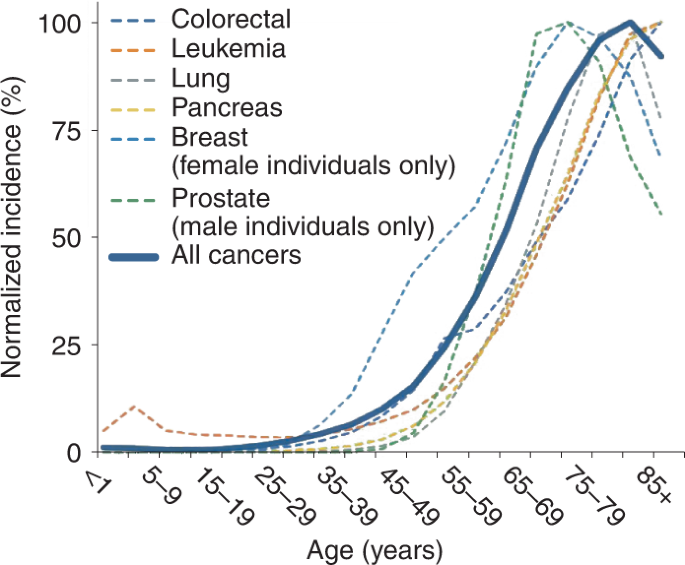

Cancers are a collection of diseases in which normal cells learn specific 'driver' mutations that lead to their transformation into highly mitotic malignant cells that form tumors and that somewhen spread to other tissues in the body. Treatments exist that can increment patient survival simply cancer remains the second leading cause of death worldwide, after cardiovascular diseases. Although cancers affect children, adolescents and young adults, most individuals are diagnosed after the fifth or sixth decade of life (Fig. 1). This historic period dependency is also reflected in mortality statistics. Globally, individuals aged 70 and older bear half of the cancer bloodshed burden (about 5 one thousand thousand deaths each year), with another 40% borne by 50-to-70-year-old individuals. Equally such cancer is considered an aging-related disease. Interestingly, many of the biological processes that underlie the hallmarks of cancer1 overlap with the hallmarks of aging2, including genomic instability, abnormal proteostasis, telomere attrition, heightened inflammation and increases in cellular senescence, thus pointing to the existence of biological connections.

Data source, SEER (https://seer.cancer.gov/statistics-network/); inspiration for this figure comes from figure 1b in ref. eleven. See ref. 11 and other interesting related works on the concept of 'adaptive oncogenesis' that propose an caption for the age-dependency of cancer incidence in the context of evolution.

Despite the clear epidemiological statistics and similarities between aging and cancer biology, most preclinical studies on cancer ignore the aging dimension of the disease. Typically, mouse studies use young animals of half-dozen–eight weeks of age3, the equivalent of approximately xv–20-year-old humans. In that location also appears to exist disconnect in clinical research, every bit older adults — in particular, those over 75 years old — are underrepresented in clinical trialsiv. This is an important issue as older patients tend to have more crumbling-related physiological decline conditions, such as frailty and sarcopenia, and more comorbidities (ofttimes leading to polypharmacy) than younger patients. All of these factors tin influence the safety, toxicity and effectiveness of treatments. Encouragingly, this important gap has but been formally recognized by the FDA, who recently issued guidelines on the inclusion of older adults in cancer clinical trials. Although trends are changing, the written report of aging in cancer is all the same very much in its infancy.

A root crusade of cancer is the conquering of somatic driver mutations in proto-oncogenes or tumor-suppressor genes. The fact that somatic mutations drive tumorigenesis is often perceived as the explanation for why the onset of most cancers takes place in middle and erstwhile age: if somatic mutations accumulate with the passage of time, getting older progressively increases the take chances of reaching the oncogenic mutation threshold necessary for cancer initiation. Although there is some truth to this, this passage-of-time explanation is likewise simple. Long-lived species, such equally the naked mole rat, some species of bats, elephants and blue whales, are cancer-resistant5 and big mammals do non have higher rates of cancers than small ones6, despite comprising much larger numbers of cells (something known as Peto's paradox). This points to the fact that animals have evolved various tumor-suppressing mechanisms, many of which remain to be identified. Interestingly, a recent written report has likewise shown that somatic mutations tend to accumulate more slowly in long-lived mammalian species, suggesting that somatic mutation rates themselves are subject area to evolutionary constraints7. Altogether, these observations propose that the age dependency of cancer incidence is not simply the result of the passage of time, but that it is besides partly adamant by biological forces (which themselves are probably affected by aging).

Another slice of the age-dependency puzzle in cancer comes not from the biology of cancerous cells but from their aged environment. In that location has been accumulating bear witness that the 'tumor microenvironment' has a deterministic office in the acquisition of cancer hallmark traits1,3. Several types of nonmalignant cell (including fibroblasts, and endothelial, immune and stem cells) in the tumor stroma and its vicinity are not simply bystanders, but instead collaborate with precancerous and cancerous cells to contribute to the initiation and progression of tumorigenesis. There is increasing evidence that biological changes associated with aging shape the influence of tumor-associated stromal cells on the course of the diseaseiii. For example, it was recently discovered that inducing cellular senescence specifically in the stroma to mimic biological crumbling creates a chronically inflamed tumor-permissive surroundingsviii. It was likewise recently constitute in a mouse model of melanoma that aged fibroblasts can bulldoze lung metastasis and therapy resistancenine, as well as the awakening of dormant metastatic cells. Beyond the tumor microenvironment, the systemic environment also changes with historic period in ways that can promote tumor progression10. Thus, it is condign increasingly clear that many factors linked to the biology of aging and the historic period of the host contribute to an environment that not only can promote tumor initiation but also influence tumor progression and metastasis, and even bear upon resistance to cancer treatments.

If we are to understand cancer in all its complication and develop new and better therapeutic approaches to assist patients with cancer, it is essential to better understand the part of the aged environs in cancer development and in the response to handling. Information technology is as well of import to collect more clinical data on therapeutic outcomes in older patients and so as to meliorate inform clinical practise in a geriatric context. Nature Aging is interested in recognizing and supporting all these efforts. We encourage researchers who study the intersection of crumbling and cancer in the laboratory (every bit exemplified in a higher place), in the clinic or in societal contexts to consider submitting their piece of work to the journal.

References

-

Hanahan, D. & Weinberg, R. A. Cell 144, 646–674 (2011).

-

López-Otín, C. et al. Cell 153, 1194–1217 (2013).

-

Fane, M. & Weeraratna, A. T. Nat. Rev. Cancer 20, 89–106 (2020).

-

Singh, H. et al. J. Clin. Oncol. 35, no.15_suppl. 10009 (2017).

-

Seluanov, A., Gladyshev, V. N., Vijg, J. & Gorbunova, V. Nat. Rev. Cancer 18, 433–441 (2018).

-

Vincze, O. et al. Nature 601, 263–267 (2022).

-

Cagan, A. et al. Nature 604, 517–524 (2022).

-

Ruhland, M. One thousand. et al. Nat. Commun. 7, 11762 (2016).

-

Kaur, A. et al. Nature 532, 250–254 (2016).

-

Gomes, A. P. et al. Nature 585, 283–287 (2020).

-

Laconi, E., Marongiu, F. & DeGregori, J. Br. J. Cancer 122, 943–952 (2020).

Rights and permissions

Near this article

Cite this article

The importance of aging in cancer research. Nat Crumbling 2, 365–366 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43587-022-00231-x

-

Published:

-

Event Date:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s43587-022-00231-10

Source: https://www.nature.com/articles/s43587-022-00231-x

Posted by: allenmignobt.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Is It Valid To Study Aging Pathologies In Young Animals?"

Post a Comment